The challenges of dry summers and increasing input prices have tempted one East Lothian beef farmer into trying out fodder beet for finishing his beef cattle.

And Anderson Waddell has no regrets, and for now, he’s committed to a crop each year. In May 2023, his contractors sowed six hectares of plant breeder Limagrain’s Robbos fodder beet and lifted about 120 tonnes per hectare fresh weight (50t/acre) of the crop in November. He’s recorded good intakes of this high energy feed and found an improvement in the finished cattle.

Anderson runs the 150-hectare beef and arable family farm at Pencaitland, East Lothian, 14 miles southeast of Edinburgh. He buys about 90 six-month old male calves, mainly from one farmer, between October and December each year. Most are pure Charolais, and the rest – about 25% – are Limousin.

Anderson runs the 150-hectare beef and arable family farm at Pencaitland, East Lothian, 14 miles southeast of Edinburgh. He buys about 90 six-month old male calves, mainly from one farmer, between October and December each year. Most are pure Charolais, and the rest – about 25% – are Limousin.

These calves go out to grass the following spring at around 300kg liveweight and are then housed from 430kg to finishing weights of 650kg to 700kg.

Indoors, cattle get a diet of grass silage and homegrown barley in troughs which this year has been mixed with chopped fodder beet.

“By October each year I can have about 280 cattle on the farm, so I need a reliable source of high quality feed,” he says, adding that the dry summers have knocked back silage yields and increasing input prices have affected the cost of growing barley.

“So I was keen to look at alternative home grown feeds to eke out supplies of silage and reduce my reliance on feed barley. I am to be self-sufficient in feed supplies.”

Many friends in the area grow fodder beet so Anderson asked around for some tips and took the recommendation from his seed merchant Dods of Haddington.

“The reliability and consistency of fodder beet yields, and its feed value made it an attractive option, and the variety Robbos, which is tried and tested was recommended and a lot around here grow it,” he adds. “So it seemed like a good option to start with.”

The crop was sown into prepared land following barley. Anderson applied plenty of dung on the stubble prior to ploughing and preparing the seed bad.

“Input costs after sowing were relatively small – just three weed treatments were applied between May and June. Establishment was good and despite some dry conditions, the crop kept growing.”

His contractor lifted the crop in November – which Anderson admits was a bit late in view of the wet conditions. “But it yielded well and it’s certainly taken pressure off the silage and barley. Cattle have grown well and they’re killing out better.”

He wants to improve the chopping equipment – last winter he used a Ritchie Root bucket feeder, which was not ideal. “I’ve still a bit to learn with growing and feeding fodder beet but it’s just what I needed in the diet and it’s cost-effective,” he adds.

“And I also have plenty of organic matter on the field to promote soil health ahead of the next crop of spring barley that will be drilled in May. So, fodder beet is giving me just what I wanted from a forage crop – it’s a win-win for now.”

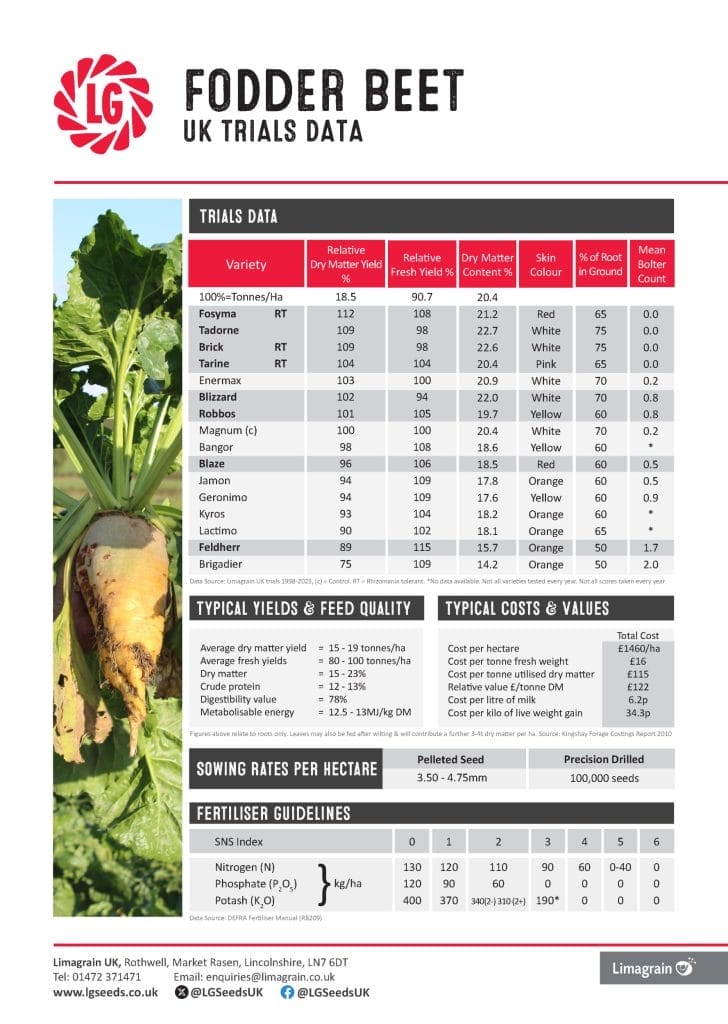

Find out more about Robbos fodder beet here and download our latest UK trial results for fodder beet.

Don’t forget about Fodder Beet!With feed costs continuing to rise, why not consider growing a crop of Fodder beet?

Yielding between 80-100 tonnes of fresh feed per hectare, growing a crop can help reduce your winter feed purchases. It’s not too late to drill, early crops are usually drilled early April but this year’s weather means many crops won’t be drilled until end of the month or even into the first week of May.

won’t be drilled until end of the month or even into the first week of May.

Later drilling may also help reduce bolter numbers. You should try to drill 100 – 110,000 seeds per hectare, with a view to establish 80 – 100,000 plants per hectare at harvest. Drill widths range from 45-50 cm with seed spacings of 15-20cm. Seedbed conditions are vitally important, with a requirement for a fine, firm seedbed with a soil temperature above 5˚ C.

With rotational options limited in some regions, Fodder beet will allow you to drill barley, or a grass reseed in the spring and also help fill any feed gaps that may have appeared this spring.

CHECK OUT OUR BRAND NEW FODDER BEET VIDEOS OVER ON OUR YOUTUBE CHANNEL

Beef growth rates boosted by high value maize

Maintaining target growth rates in a beef finishing enterprise requires a year-round ration that is well-balanced, high in energy and easily digestible. For Yorkshire farmer Edward Liversidge, based at Primrose Hill Farm, High Catton, the key is to feed a total mixed ration based on high quality maize, with the crop being grown as a fully integrated part of the farm’s arable rotation.

Success comes from the Liversidge family’s years of experience of growing maize and it starts with selecting the right variety for the job.

“First and foremost, we want a variety that is going to perform in our situation, which means it needs to be compatible with our soils and location,” says Edward. “Alongside this, we’re looking for good D-value, ME and starch, because it’s the nutritional value that will drive growth rates.”

York-based agricultural trading company Argrain are the Liversidge’s seed suppliers, with seed specialist Lucy Leedham being trusted to make the right recommendations due to her local knowledge and experience. For the 2023 season, she introduced Limagrain’s first choice early variety Conclusion, highly ranked for ME yield and cell wall digestibility and with the right maturity class for this area.

“Conclusion has performed well in our local trials, and we’ve generally had good feedback on it in our area,” says Lucy. “It’s a very good all-round variety, offering the combination of high yields alongside nutritional quality that this farm demands. It also has the attributes to be grown successfully for grain, in that it is not quick die back and has good standability, which is an option that I know the Liversidges like to have.”

Growing as much as 150 acres of maize each year, the policy at Primrose Hill Farm is to grow two varieties, partly to spread risk, but they do it in a way that ensures a consistent feed is available all year round.

“We tend to split the contractor’s 8-row drill to grow alternating 4-row strips of two different varieties, which – when cut with a 12-row forage harvester – creates a consistent blend in the clamp,” explains Edward. “We’ve combined Conclusion with another high energy variety of similar maturity and achieved an overall fresh weight yield of between 19 and 20 tonnes/acre.

“It’s analysed as we’d hoped, with high starch and digestibility, and is feeding well. It’s exactly what we need to achieve our target growth rates.”

The majority of the maize grown at Primrose Hill Farm is in rotation within the arable acreage, and usually follows an over-winter cover crop that will have been grazed by sheep on tack. The cover crop is geared to meeting the needs of all parties, including the grazier, and would typically include grazing rye and stubble turnips.

Once cover crops have been grazed off, there is plenty of time to spread farmyard manure and prepare a seedbed ahead of maize drilling, which will usually be towards the end of April. One of the routine jobs well ahead of drilling is soil sampling, with the analyses being used to determine any additional fertiliser applications.

“We’re testing our soils in order to create soil nutrient maps, which then allows us to apply phosphate and potassium at variable rates,” adds Edward. “We’ve been doing this for three or four years now, to improve our use of fertilisers and save costs where we can.

“We’re also applying a slow-release liquid nitrogen pre-emergence. This ensures that the crop can draw on nutrient reserves in the soil at the important growth stages, well beyond the point where it’s possible to drive into the crop to top-dress with a granular fertiliser.”

Herbicides are used according to the weed burden in any particular crop, with either one or two applications required.

With nutritional value of the maize the main priority, harvest is determined by cob maturity, and took place in 2023 just before the end of September. It was a bumper crop, and with the clamps at Primrose Hill Farm full, the decision was taken to cut some of the maize for grain.

“We used a local contractor’s machine with a specialist header to harvest some of the maize for crimping,” says Edward. “This worked out really well and, thanks to the Conclusion being suited for taking as either grain or silage, has given us an additional high energy feed for the ration.”

“We used a local contractor’s machine with a specialist header to harvest some of the maize for crimping,” says Edward. “This worked out really well and, thanks to the Conclusion being suited for taking as either grain or silage, has given us an additional high energy feed for the ration.”

The Liversidge’s cattle enterprise involves buying in strong stores, usually British Blue or Angus crosses from dairy herds in the 400 to 500kg range. These are finished on a total mixed ration, to achieve finished liveweights of 670-720kg.

“We aim for a finishing period on the farm of 90-120 days, so we need a ration that is going to drive good growth rates,” concludes Edward. “Good quality maize silage is the basis for the ration, so growing a mature crop is essential. Success with the maize crop means the bigger proportion of what we’re feeding the cattle is homegrown.”

Modern fodder beet suits arable rotation and provides essential livestock feedBrothers Richard and Fred White who run a 650-hectare mixed farm have grown fodder beet as part of their crop rotation for the past 23 years

Brothers Richard and Fred White run a 650-hectare mixed farm, comprising beef, sheep and arable enterprises, in Warwickshire, and they’ve grown fodder beet as part of their crop rotation for the past 23 years, waxing lyrical about its record yields and its part in ticking a lot of boxes in their farming system.

They began growing Limagrain UK variety Fosyma in 2020 after a recommendation from Wynnstay’s Emma Edwards. This high-dry-matter fodder beet variety is pink-skinned and conical-shaped, and it combines a dry matter content of between 20% and 21% with a relatively high proportion of its root (40%) out of the ground, leaving just 60% in the ground.

Essential part of the rotation

“It fits well into our rotation, usually following and preceding winter wheat,” explains Richard. “We also grow forage maize to feed to the 180-head beef herd, as well as oats and barley, which is also rolled and fed to livestock.”

He and Fred thought Fosyma would do well on their Tamworth-based farm, particularly because they lift and feed fodder beet to their Hereford cattle and sheep during the winter.

It’s medium-depth root reduces the risk of soil contamination and offers flexible feeding and end-use options. Their contractor uses root-lifting equipment, typically harvesting the 23 hectares of the crop that they grow each year. Soil contamination has never been an issue for the Whites.

Market options

They store and feed approximately 50% of the fodder beet to their own sheep and cattle. The other half is sold off farm, for between £45 and £50 per tonne. Some has gone to AD plants, and some has also been sold to feed to deer om a nearby estate.

“They really enjoy fodder beet – as do our cattle and sheep. They all do really well on it.”

Producing home-grown feed and forage is a priority for the brothers, but fodder beet is also a useful break crop. “We typically sow is at the end of April, after applying plenty of manure,” explains Richard, adding that the farm comprises a mixture of different soils.

Producing home-grown feed and forage is a priority for the brothers, but fodder beet is also a useful break crop. “We typically sow is at the end of April, after applying plenty of manure,” explains Richard, adding that the farm comprises a mixture of different soils.

“We have heavy, medium and light soils and the crop is sown across them all – we mix it up. And is performs well – we always see good yields.”

Once in the ground, Richard says the fodder beet ‘doesn’t hang about’. “It germinates and grows quickly. We do need to control weeds, to prevent competition, but once well established the crop’s canopy helps to suppress them.”

The crop is typically ready for harvest at the end of September, but they leave it in the ground until lifting in mid-October. As soon as the beet is lifted, they’re ready with the drill and sow winter wheat into the ground. So they’re not leaving the land fallow over winter.

Palatable yields

For the past three years Fosyma has yielded between 30 tonnes and 35 tonnes per acre (75 tonnes and 87 tonnes per hectare). It’s stored outside in a clamp made from straw bales and feeding to outwintered livestock starts when grass growth slows, which is usually at the end of October.

“It’s fed whole, on the ground, to cattle and sheep. We don’t have to chop it. And they love it – there’s no waste.”

Richard adds that as well as adding ‘interest’ to winter rations, fodder beet also supports lamb growth.

The 450-ewe flock lambs in late April, and lambs are finished on the farm’s 400 acres (160-hectares) of permanent pasture and fodder beet during the winter. “We start selling lambs in January, at around 45kg LW,” he says.

The 450-ewe flock lambs in late April, and lambs are finished on the farm’s 400 acres (160-hectares) of permanent pasture and fodder beet during the winter. “We start selling lambs in January, at around 45kg LW,” he says.

Home grown forage saves £

“We don’t buy in any feed or concentrates for the ewes or the lambs – the system is completely forage based.”

The beef enterprise is also predominantly grass based, with only home-grown cereals fed as part of winter ration when cattle are housed. Cattle are finished and sold, at between 24 and 30 months, to local butchers in Atherstone

In 2021, Richard grew a crop that looked very ‘bare’. “The seed went in well, as usual, but were no beet plants and there were no weeds either. It was odd and Limagrain UK’s Brian Copestake came to take a look because I was at a loss as to what had happened.

“He said it was a flea beetle problem and while I was deliberating about re-drilling, the field suddenly sprouted green rows of beet plants. It soon caught up and within weeks we had a field full of strong and healthy beet that as well up to calf level. It bounced back well and I don’t think I’ve ever seen any other crop do that.”

All-weather crop

Fodder beet also performs well in both wet and dry summers. “We noticed how much deeper rooted the crop was in 2022, due to the drier than typical conditions. It tolerated the more extreme summer and actually outperformed the 2021 crop.

We harvested 98 tonnes per hectare, which we were extremely pleased with,” says Richard, adding that poorer performing crops of different fodder beet varieties have yielded just half that at 50 tonnes per hectares.”

The Whites are planning to grow a similar hectarage of Fosyma in 2023.

“The variety (Fosyma) is the best we’ve ever grown, and we’ll certainly be drilling it again in 2023. Fodder beet has been an essential part of livestock rations and the crop rotation here for 23 years, so that’s not set to change,” adds Richard.

Learn more about Fosyma fodder beet here or contact your usual seed merchant for availability

The latest UK trial results data on fodder beet (including Fosyma) can be downloaded here

Forage outlook and options for 2024The climate is keeping us on our toes and this year (2023) has been no exception. It calls for flexibility and agility when it comes to growing forage crops. Limagrain’s forage crop manager John Spence sows some seeds of ideas on future proofing home grown feed supplies going forward.

“We’re ending the year with decent stores of grass and maize silage, but this doesn’t tell the full story,” says John Spence. “A cold late spring delayed grass growth, then for most grass silage making started well, until heavy rain arrived.

Hot and dry conditions weren’t as extreme as 2022, but some were affected with poor grass growth, then some respite and good grass growth through a mild autumn until heavy rain put some areas under water at worst and at best caused the late sowing of forage catch crops which will certainly hamper their yield and quality.

Hot and dry conditions weren’t as extreme as 2022, but some were affected with poor grass growth, then some respite and good grass growth through a mild autumn until heavy rain put some areas under water at worst and at best caused the late sowing of forage catch crops which will certainly hamper their yield and quality.

So farmers are faced with balancing more extreme weather conditions and the drive to improve sustainability and economic viability by producing more feed value from home grown forages.

“Marrying the two is quite a challenge,” adds Mr Spence.

“Agility and flexibility are key when it comes to planning. Avoid planning everything in stone and being too rigid with the cropping.”

Forage choices

The dairy system will determine forage options, with more alternatives typically possible in grazing herd situations. “A herd housed full time will usually rely on conserved high quality silages. “This has to remain the priority,” says Mr Spence. “But introducing forages like fodder beet and forage rye can really boost output from homegrown forages, as well as opting for higher production grass seed mixtures and clovers.

“Grazed herds can consider kale too, and some brassicas like Skyfall that ‘bounces back’, in effect giving two grazing crops, through summer which can take the pressure off the grass.”

Fodder beet, though, has been used in dairy cow diets for many years in areas where it can be grown on farm or locally on contract.

“This is a high energy crop, highly digestible and ‘enjoyed’ by dairy cows. We’ve tested a range of varieties in our own UK farm trials for more than 10 years and yields are consistently reliable, even in dry hot summers,” he adds.

“And new modern varieties are out-performing some of the older fodder beets. Limagrain trials consistently show the variety Fosyma to have the best dry matter yield at 14% above the control variety Magnum, and 5% above its closest rival Brick.”

Fodder beet’s feed value at 78% digestibility and 13MJ/kg of dry matter is a valuable addition to any dairy ration.

Kale might have been out of fashion. “But not anymore,” adds Mr Spence. “Here again, new varieties with improved feed value have brought the crop back into the spotlight.”

He highlights Bombardier – a relatively new kale variety with a nutritious stem and leaf with 72% digestibility in UK trials and 17% crude protein It’s sown between April and June so it can follow first cut silage and provide a valuable break crop in the grass rotation.

“A kale crop can slot into the plan for many grazing herds. It’s fast-growing so cattle can strip graze it as a buffer feed in mid-summer to take the pressure off the grass.

But it has a long shelf-life too, so it’s a useful crop for youngstock and dry cows in autumn and winter. In either situation it can be used as a break crop and followed with a grass reseed. Break crops between grass crops are increasingly important in breaking the pest cycle and improving productivity of grass leys.”

Forage rye has been particularly popular this autumn – 2023, with crops following harvest or early maturing maize varieties. It can be sown until late October and is ready for cutting or grazing in early spring, even before Italian ryegrass.

A crude protein content of 12% and an ME of 10MJ/kg DM makes it an ideal forage for late lactation or dry cows, or youngstock. And once finished, the field can go back into maize or a spring reseed.

“A crop of rye will provide a valuable feed to eke out silages and it’s also a great crop to mop up residual nutrients and maintain soil health. The only caveat maybe sowing in a very wet autumn, but most farmers were in time this year, as the first half of autumn was warm and dry. So again, a flexible approach is needed and the will to act if conditions are right.”

Grass is king

Grass is the most important forage for most dairy farmers, and increasing its productivity and feed value should be on-going. This includes regular reseeding and taking advantage of improved grass seed mixtures and always selecting a grass seed mixture to suit the system and purpose of the crop, as well as the growing conditions and soil type.

“There are new varieties, improved grass seed mixtures and enhancements to match changing conditions. So farmers should seek advice and look for mixtures with proven trial results and good performance on UK farms and be discerning in their choices,” adds Mr Spence.

Limagrain trials in 2020 highlight the benefit of reseeding and of selecting proven mixtures. Table 1 highlights the productivity of a one year old ley and a four year old ley. The additional 45% of energy produced by the new sward was equivalent to more than 6,000 litres of milk (assuming 5.3MJ/litre).

Table 1

|

|

Age of Sward (Years) |

|

|

|

|

4 |

1 |

Benefit of New Ley |

|

1st Cut DM yield (t/ha) |

3.57 |

6.06 |

+2.49 |

|

ME (MJ/kg DM) |

10.8 |

11.9 |

+1.1 |

|

ME yield (MJ/ha) |

38,669 |

72,072 |

33,403 |

Source: Limagrain UK Trials, May 2020

“The additional energy yield value from younger leys will increase the proportion of milk yield from home-grown forage, reduce bought-in feed costs and this will justify the cost of the reseed. Depending on the age and quality of the ley, estimates suggest the additional yield in year one of a reseed will cover its cost.”

Trials have also demonstrated the benefits of improved mixtures with proven feed values. LGAN is the accreditation given to LG mixtures that meet the company’s combined yield and feed value criteria, and table 2 shows the performance range at first cut of the one-year-old mixtures on trial.

Trials have also demonstrated the benefits of improved mixtures with proven feed values. LGAN is the accreditation given to LG mixtures that meet the company’s combined yield and feed value criteria, and table 2 shows the performance range at first cut of the one-year-old mixtures on trial.

“The best performing mixture at first cut was LGAN Quality Silage, which produced more than 7t/DM of 12.5ME silage. The trial year, 2020, was particualrly dry, so these results demonstrate the big gains that can be made by using high-feed-value mixtures.”

Table 2

|

|

Max |

Min |

Range |

|

DM yield (t/ha) |

7.81 |

4.78 |

3.03 |

|

ME (MJ/kg) |

12.5 |

11.6 |

0.9 |

|

ME yield (MJ/ha) |

93,703 |

55,384 |

38,319 |

Stock up on clover

A forage outlook for 2024 wouldn’t be complete without highlighting the benefits of clover in grass leys.

“Any new reseed with clover in the mix or overseeding a ley with clover is eligible for an annual payment of £102 a hectare under the new SFI action NUM2 (Legumes on improved grassland),” says Mr Spence.

“This more than pays for the seed, and it brings all the benefits in soil health, nitrogen fixing and feed value. And in mid-summer, the clover provides good feed value when perennial ryegrass growth slows down.”

A lot of focus is also being placed on multispecies leys, with sustainability schemes encouraging dairy farmers to integrate them into their systems. “There are payments available under the new SFI scheme for sowing multispecies leys which will be worth investigating in the forage planning for 2024.

A lot of focus is also being placed on multispecies leys, with sustainability schemes encouraging dairy farmers to integrate them into their systems. “There are payments available under the new SFI scheme for sowing multispecies leys which will be worth investigating in the forage planning for 2024.

“There is a lot of considerations and it’s worth having an open mind to new ideas and options.”

FORAGE PLANNING POINTERS

- Plan to increase output from homegrown forages

- Throw the net out wider – look at all the options

- Have a flexible plan and be agile to adapt to the season’s weather conditions

- Have a robust and productive rotation for the farm – no one rotation fits all

- Use a forage break crop between grass reseeds

- Look at improved forage crop varieties with better protein and energy contents

- Clover in grass leys is a must

- Improving grass quality and feed value is on-going

- Carefully select grass seed mixtures with proven feed value

For more info on forage options to suit your farm business, click here or download the LG Essential Guide to Forage Crops

King of the cropLG Monarch grass seed mixtures come up trumps on North Yorkshire sheep farm

Livestock farmer Andrew Hollings relies on good quality grass for his 1,000 hill ewes and small beef herd situated in Goathland, in the North Yorkshire National Park.

The farm is a mixture of moors and lower lying grass leys. Andrew, who is the third generation of the family to farm at Liberty Hall, has a system designed to suit the area. His Swaledales and Cheviots are hardy enough for the moors. These are crossed with a Leicester tup, and the lambs are reared and finished on the lower land. Lambing starts in early April.

“It’s soon enough up here,” says Andrew, who has noticed a change in conditions during his farming career. “We’ve always worked with the weather not against it,” he adds.

“We’re just 10 miles in land from Whitby and we seem to get stronger winds coming off the North Sea,” he says. “These winds are our biggest challenge. It can be very wet, then the winds pick up and they dry out the ground. Summers are drier and warmer than they were 30 years ago. These conditions are harsh on the grass crops. We have to adapt our system to maintain and improve productivity.”

Mindful that grass must remain ‘king’ on both Liberty Farm’s 93-hectares and the blocks of rented land, Andrew has become more discerning on grass seed mixture choices and he’s started using options that are more suited to conditions and to coping with the challenges, all while improving feed value and productivity.

“I want as much feed value from homegrown forages,” he adds. “I rely mainly on grazed grass and some haylage. In very dry summers, we’ve seen the ground dry up and grass becomes short. In 2022, when it was particularly dry, the feed value in the grass dropped and ewe productivity fell and there were more single lambs.”

The knock-on effect of this changing weather pattern has made Andrew look more carefully at improving grass productivity to safeguard home grown forage supplies. And it’s seen a move to better quality grass seed and multispecies mixtures.

He’s taken some advice from BATA’s agronomist Rose Thompson, and in 2021, he moved to using LG Monarch mixtures; partly because their range has mixtures designed for specific environments and purposes and also because the mixtures, designed by seed breeding company Limagrain, have been tried-and-tested in UK conditions.

“I look to reseed 15 to 20 acres (six to eight hectares) a year,” adds Andrew. “Grass is the cheapest feed we have. If I can improve the quality, it pays dividends.”

He opted for LG Monarch FlexiScot, which is a long-term mixture with highly productive tetraploid and diploid rye grasses, for early growth, and Timothy and white clover varieties that mature in mid-summer and offer some drought resistance.

This mixture has excellent winter hardiness, and it has been tested successfully, across Scotland and Northern England.

Andrew directly drilled the Flexiscot seed after a crop of stubble turnips which were grown as a break crop. “We put plenty of muck on the land and a bit of fertiliser when we shut it up – this is hungry land.”

In fact, Andrew soil tests the land every year. “It’s vital that we get the pH right – it’s acidic soil and we need to lime it regularly, applying about 3t/acre (1.5t/ha).”

The resulting crop was highly successful and produced a dense sward that came out very well when analysed as part of the farm’s Flock Health Plan. “It’s a mixture that I will continue with – the yield and quality in year one and two has been phenomenal.”

Sheep at Liberty Hall graze the lower-lying grass swards until mid-May when they are closed up for six weeks before cutting for haylage for feeding ewes in January to March when there’s no feed value in neither the grass nor heather.

“I’m really pleased with the amount of grass we get off it,” he adds. “The swards are yielding very well with good quality grass and they’re lasting well through summer. This mixture is a big improvement on the previous ones.”

Another mixture Andrew introduced just recently is LG Monarch Multi-species. This medium-term herbal ley grazing mixture includes later perennial ryegrass, Timothy, red and white clover, chicory, sainfoin, fescues and plantain. The legume varieties reduce fertiliser input requirements and drought resistant species see the crop thriving during summer.

“I sowed 13-acres (5-ha) in mid-September 2022 – just power-harrowed the field and disced in the seed. It grew well. It didn’t need fertiliser, there were no growth checks. It was ready for grazing in spring and the sward remained very green throughout the summer.

“I sowed 13-acres (5-ha) in mid-September 2022 – just power-harrowed the field and disced in the seed. It grew well. It didn’t need fertiliser, there were no growth checks. It was ready for grazing in spring and the sward remained very green throughout the summer.

“In fact, it grew so vigorously early in the season, that we had to cut and bale some. The aftermath went on to make excellent grazing right through summer for the lambs. We’ve grown more multicut now – it’s an ideal mixture for our lower-lying fields.

“These improved mixtures prove that it’s not what the grass seed costs, but it’s what it does that’s important.”

IDEAL FEED FOR SHEEP

Limagrain forage crop account manager, Henry Louth, says that Mr Hollings’s experience with specific LG Monarch grass seed mixtures demonstrate the mixture’s potential to work well in harsher conditions.

“This makes them ideal for upland sheep farmers,” he says.

“Limagrain promotes its LG Monarch range, particularly the Flexiscot, Multicut and Multigraze mixtures to sheep farmers. Not only do they grow well, even in less than perfect conditions, they provide high feed value. Sheep and cattle also do particularly well on these forages.”

He is also seeing more interest in the Monarch Multi-species mixture. “This is ideal for low-input grazing, and it provides a grazing crop throughout summer and in drier conditions. As the grass growth slows down, other varieties in the mixture, like chicory, keep growing.”

Find out more about our grass mixtures here

Regenerative principles support more productive grasslandA longer growing season, better quality grass and improved pest control support overall forage production, and they are all advantages of following regenerative agriculture principles.

“One key pillar of regenerative agriculture is greater plant diversity,” says Limagrain’s forage crop manager John Spence. “And it’s an area where grassland farmers can reap the benefits by growing mixtures with more species that widen the growing period and help to combat more variable climate conditions.

“For example, clovers continue to grow in mid-summer when ryegrass varieties slow up. This increases the growing season. Clover also offers nitrogen-fixing benefits.”

Likewise, deeper rooted plants included in multi-species mixtures, such as chicory and plantain, will be more productive in drought conditions whilst also improving soil structure and health.

Improve ground cover

Keeping soil covered is another regenerative pillar – and one to focus on for improved grassland productivity. “Mixtures with improved ground cover, dense swards and few bare patches are less prone to poaching in winter on wet land,” he adds. “Including clovers and herbs alongside highly productive ryegrass varieties ensures mixtures are more robust in dry summers with good ground cover, as well as increased forage output and quality.

He encourages grassland farmers to avoid leaving swards fallow between reseeds. “We recommend that farmers avoid following grass with grass immediately, particularly if there’s a pest problem, and a six-month break is good. Instead, a winter forage crop such a stubble turnips and forage rape will maintain ground cover, help to break the pest cycle, and provide extra much-needed forage for livestock.”

He encourages grassland farmers to avoid leaving swards fallow between reseeds. “We recommend that farmers avoid following grass with grass immediately, particularly if there’s a pest problem, and a six-month break is good. Instead, a winter forage crop such a stubble turnips and forage rape will maintain ground cover, help to break the pest cycle, and provide extra much-needed forage for livestock.”

One of the main regenerative agriculture pillars is avoiding soil disturbance. “For grassland farmers this means direct drilling of new leys, minimum soil cultivation, and avoiding ploughing where possible. Overseeding is a good way of increasing productivity without cultivation”.

“Mixtures with tetraploid ryegrasses are good here as they complete well with existing grasses.”

Grassland farmers are already following many of the regenerative farming principles, but there’s more to be gained – specialist mixtures, forage break crops and improved practices will both support soil health and add to grassland productivity.

Financial support?

And there’s the added support from new SFI rules that could offer cash payments for making certain improvements, such as “NUM2: Legumes on improved grassland,” which offers £102/ha for introducing legumes such as white clover into existing temporary grass swards.

“It’s a win-win for many grassland farmers – more output from grassland and increased support for regenerative principles will support their businesses’ longer-term sustainability.”

Find out more about our grass mixtures here

Post harvest options – Food for thoughtA post-harvest catch crop can be a win-win for sheep producers. Crops such as stubble turnips, forage rape, forage rye and brassica mixtures produce high quality autumn and winter feed cost-effectively.

“Stubble turnips, forage rape and rape/ kale hybrids can be sown up until the end of August,” says Limagrain UK’s Martin Titley. “They’re quick to establish and some varieties can be ready for grazing within 12 weeks of sowing. Hardier varieties can be left for grazing over winter.

Rape/kale hybrids like Interval is an example of a fast-growing catch crop. “In our recent trials, it has produced yields 16% above the control. It’s an ideal crop for finishing lambs or for maintenance from late summer onwards,” he adds.

Rape/kale hybrids like Interval is an example of a fast-growing catch crop. “In our recent trials, it has produced yields 16% above the control. It’s an ideal crop for finishing lambs or for maintenance from late summer onwards,” he adds.

Limagrain quotes growing costs of forage rape of £408 per hectare with dry matter yields between 3.5 and four tonnes per hectare.

Stubble turnips cost £305 per hectare to grow with dry matter yields per hectare between 4 and 5.5 tonnes. “This crop makes an ideal feed in the autumn with hardy, mildew resistant varieties ideally suited to grazing through winter.”

And he suggests looking at brassica mixtures too. “Sheep producers can make things easier with these mixtures. Autumn Keep and Meat Maker, for example combine a high protein forage rape with kale, blended with a high-energy stubble turnip to provide a balanced autumn and winter keep with minimal effort. Advantages such as disease resistance, winter hardiness and early establishment have been ‘built-in’ too.

“And it is worth spending some time looking at the varieties on offer. Our annual trials compare yield and disease resistance of varieties of catch crops and the results can highlight significant differences.

“For example, there is a 20% yield difference between some stubble turnip varieties and this equates to more than one tonne of dry matter per hectare. Samson is one of the top yielding varieties in the trial with a dry matter yield of 5.76 tonnes per hectare and, as a bonus, this variety is preferentially grazed by sheep in grazing trials.”

A catch crop will also mop up any available nutrients, returning them to the soil via the manure of grazing animals. This helps to improve soil organic matter and structure.

“Catch crops bring many advantages to the mixed farm in providing a valuable feed and added benefits to the soil. They make an excellent break crop and a perfect entry back to a grass reseed in the spring.”

More information

Learn more about these catch crop options here or contact your usual seed merchant for availability

Download the LG Essential Guide to Forage Crops below

Clover is all the rage, but watch the caveats

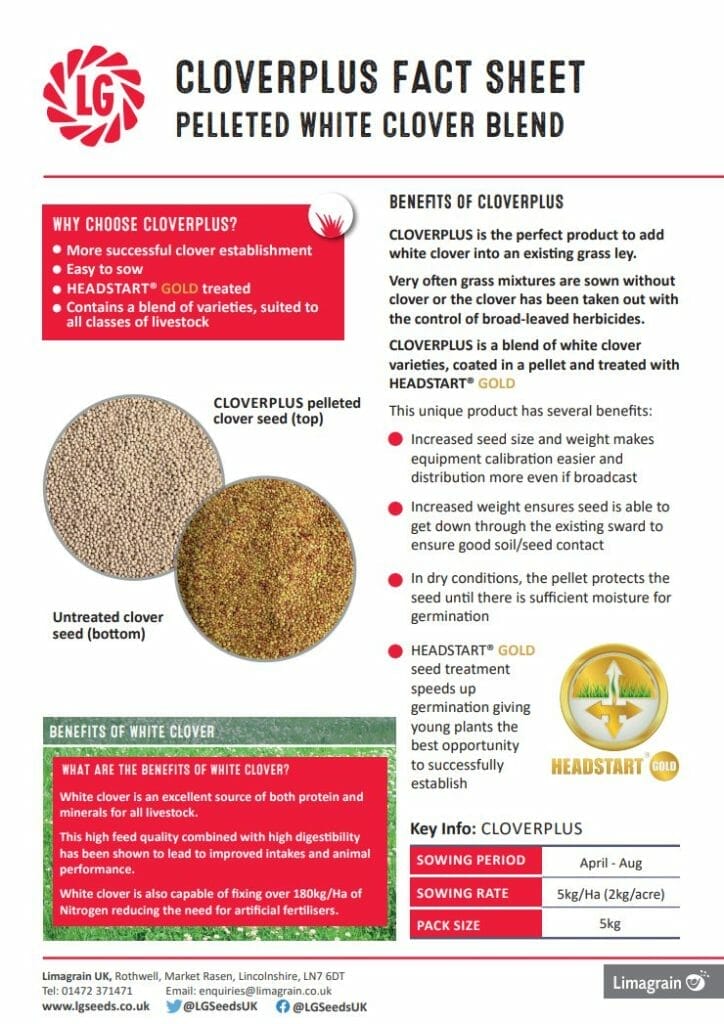

Clover mixes have been in high demand in the past few years. In 2022, Limagrain reported a five-fold increase in demand for its CloverPlus blend.

Forage crop manager John Spence considers this a wise choice, as long as growers adhere to some specific sowing and management ‘rules’ to ensure success.

Few need a recap of the advantages of clover in a grass sward. “Nutritional benefits and nitrogen fixing abilities are big attractions,” says Mr Spence. “Also, its soil health improvement potential and drought resilience add to its benefits.”

He finds it surprising that more farmers and growers haven’t taken advantage of clover until more recent years, particularly as inorganic fertiliser use has been falling on UK livestock farms since the early 1980s.

Nitrogen applications have halved on grassland farms, according to Defra reports, but only 13% of livestock farms include clover in all their leys, and 25% include no clover at all.

“This is surprising when you consider the high protein content of clover and its palatability in grass swards. On farm trials have shown that the D value in grass and white clover swards remains at least 2 points higher than a grass plus nitrogen fertiliser sward throughout the grazing season.”

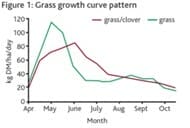

And clover’s seasonal growth also compliments grass, as shown in Figure 1. It has a deep tap root to withstand drier conditions, so a grass clover sward will have a more even growth pattern through summer.

Fig 1

A grass sward with good white clover content can produce as much forage as a grass-only sward receiving 180kg of nitrogen per hectare. “This is equivalent to 520kg of ammonium nitrate fertiliser a hectare and worth about £220 per hectare based on current fertiliser prices of £420/t.”

Red clover is more impressive and can fix up to 250kg of nitrogen per hectare, but even at 200kg per hectare, this is worth £240 a hectare.

White clover is commonly used in grazing leys, though the popularity of red clover in shorter term silage mixtures is growing primarily to increase protein content. Also red and white form a major part of most multispecies and herbal grazing leys.

Mr Spence points out important considerations when sowing clover. “Clover isn’t as vigorous as grass, so it needs careful sowing to promote establishment. The main hurdle is soil temperature. Clover will only grow when soil temperatures are above 8°C, whereas grass will germinate at 5°C. If it’s too cold for the clover, it will be outcompeted by the grass species.”

The combination of needing warmer soil temperature, plus the loss of clover safe herbicides have put growers off using clovers in the past. “Although these issues still remain, an increased focus on soil health and the recent surge in fertiliser prices have seen growers coming back to clover.”

To ensure success, clover is best sown in May or June. It can be oversown into a grass sward that has been cut or grazed tightly, so that competition from the existing sward is minimised.

The ground must be prepared by harrowing to remove any dead thatch, and to ensure good seed to soil contact.

If reseeding is scheduled for late spring, after first cut silage or a first round of grazing, then clover can be included in the grass seed mixture. “But, again, soil temperatures must be high enough and it must be sown into a carefully harrowed fine tilth to speed up its establishment and ensure it can compete with the grasses in the mix.

A biostimulant seed treatment will also help to improve germination.

Clover seed is small, and so has limited energy reserves, making establishment trickier, particularly when sown into the competitive environment of an existing grass sward.

“But establishment rates can be increased significantly (by using a pelleted and treated seed.

“This makes the seed larger and heavier so increasing the likelihood of good soil contact. It also helps to achieve better distribution when the seed is broadcasted, and it is easier to calibrate. Pelleted seed is by far the preferred type of seed for oversowing clover into existing swards.”

Seed choice

There are a range of clover varieties that can be blended to take advantage of the merits of each. White clovers are generally categorised as small, medium or large leaved types.

The smaller leaved varieties are slower to establish and lower yielding but are the most long lasting and persistent under tight grazing. Larger leaved clovers are the fastest to establish and highest yielding but are less persistent.

“Blends formulated for dairy systems tend to take advantage of the higher yielding medium and large leaved clovers,” he says. “We include 90% medium and large leaved clovers in our pelleted CloverPlus blend and only about 10% of small leaved clover to help increase ground cover and persistency. It also includes the new large leaved New Zealand variety Kakariki which gives exceptional yields.”

“Blends formulated for dairy systems tend to take advantage of the higher yielding medium and large leaved clovers,” he says. “We include 90% medium and large leaved clovers in our pelleted CloverPlus blend and only about 10% of small leaved clover to help increase ground cover and persistency. It also includes the new large leaved New Zealand variety Kakariki which gives exceptional yields.”

Overall, well-managed clovers in the sward will last for the persistency of the mixture. “White clover is very persistent and if correctly managed would last longer than many mixtures,” adds Mr Spence.

“Red clover will last three to four years and so is usually paired with grass species that last the same amount of time. For example, a grass and red clover mixture would tend to include high a proportion of hybrid ryegrass.”

Even at lower fertiliser prices, Mr Spence believes the increase in demand for clover will continue. “Persistency in drier conditions, nitrogen-fixing properties and soil health benefits as well as feed value are high on the radar for dairy farmers going forward,” he says.

Environmental schemes such as SFI are also encouraging the use of clovers, either as part of a legume rich sward, or as a tool for managing grassland with low nutrient input.

“There’s a lot of work going on behind the scenes among seed breeders too, to boost the yield and persistency of clovers, and there are new improved varieties out every year.

“I’d encourage livestock farmers to give it a go, or to introduce more clover if it’s an option, and if the guidelines are followed for ensuring good establishment, the crop will bring many benefits to animal production and to the sustainability of the system.”

Find out more

To download the CloverPlus fact sheet, click here

Start your grass planning now!

Start your grass planning now!

Autumn can be an excellent sowing period to establish a new reseed, especially if your existing paddocks look like they are running out of steam!

A few simple steps before sowing can make a huge difference:

1. A pH of 6.0 to 6.5 (for clover leys) is ideal

2. Prepare a firm fine seedbed 5-8 cm deep

3. Ring roll to ensure moisture retention and an even drill depth

4. Drill with a harrow/seeder no deeper than 6mm

5. Rolling after makes a big difference

We recommend using Sinclair Mcgill seed mixtures:

We recommend using Sinclair Mcgill seed mixtures:

Castlehill – A long term dual purpose permanent pasture with clover

Turbo – Ideal for paddock grazing systems, fast regrowth and longer grazing periods.

Colossal silage – a shorter term mixture to produce quality silage yields.

Click here to find your local Sinclair McGill distributor!

Early sowing pays off for stubble turnips

We’ve taken a look back on this 2017 trial of stubble turnips to show the advantages of sowing early – ideal for after cereals!

In a Limagrain field trial, on its innovation site in Lincolnshire, three crops of Samson stubble turnips were sown at two-week intervals from July 28, 2017. Fertiliser was applied at 35kg of nitrogen per

Samson stubble turnips

hectare, in the form of 20:10:10, into the seedbed. Crops were harvested by hand in mid-December and weighed. “The results showed that the highest dry matter yields came from those crops sown earliest,” says Limagrain forage crop director Martin Titley. “Dry matter loss was 33% in crops sown two weeks later and 59% in crops sown four weeks later.” Table 1 shows the dry matter yield from the three crops.

TABLE 1 Dry matter yield of Samson stubble turnips t/ha

| Sowing date | 28/7/17 | 15/8/17 | 31/8/17 |

| Samson | 6.6 | 4.4 (-33%) | 2.7 (-59%) |

The trial also highlighted the change in the ratio between leaf and bulb yield over time with those earlier sown crops producing higher yield of bulb to leaf compared with later sown crops. Table 2 shows the ratios of dry matter yield of bulb to leaf across the three sowing dates.

TABLE 2 Percentage Dry matter yield leaf:bulb

| Sowing date | 28/7/17 | 15/8/17 | 31/8.17 |

| Leaf % | 24% | 41% | 62% |

| Bulb % | 76% | 59% | 38% |

Limagrain has used the AHDB relative feed value calculator for stubble turnips of £123.95 per tonne of dry matter, based on feed barley at £120 a tonne and rape meal at £195 a tonne, to illustrate the difference in feed value between the three sowing dates. “The earliest sown crop of Samson has a feed value of £483.40 higher than the crop sown in late August,” adds Mr Titley. “The growing costs of all three crops is the same.” “While this trial shows the yield advantages of earlier sowing, growers should remember that all crops of stubble turnips provide a valuable feedstuff, with later sown crops providing a useful amount of leafy forage.” Stubble turnips are an ideal crop after cereals with only light cultivation required ahead of drilling. They are a fast-growing catch crop, easy to eat and highly palatable that can be grazed by sheep or cattle within 12 to 14 weeks from sowing. “If the timing of the cereal harvest allows a crop of stubble turnips to be sown earlier then there are likely to be yield advantages, but even at the end of August or early September, this crop will still provide a cost-effective forage crop.”

Stubble turnips – yield and feed value

Average DM yield 3-6t/ha

Average fresh yields 38-45t/ha

Dry matter 8-9%

Crude protein 17-18%

Digestibility 68-70%

ME 11MJ/kg DM

For all the up-to-date growing costs and growing information, download the Essential Guide to Forage Crops

LG Essential Guide to Forage Crops

LG GatePost Newsletter – June 2023

The June 2023 issue of LG GatePost is now available to download.

This edition features articles about our newest wheat addition to the 2023-24 AHDB Recommended List, LG Redwald, as well as LG Caravelle, our excellent 2-row winter feed barley.

You can read about and view our Live Panel event which was a round table discussion on Varieties, Soils and Policy with industry experts.

We discuss the new Sustainable Farming Incentives and the new ‘actions’ involved, with an article about why to consider establishing a legume fallow.

There is also information about our upcoming Demo Days and a link to register.

LG GatePost – June 2023

To ensure success, clover is best sown in May or June. It can be oversown into a grass sward that has been cut or grazed tightly, so that competition from the existing sward is minimised.

To ensure success, clover is best sown in May or June. It can be oversown into a grass sward that has been cut or grazed tightly, so that competition from the existing sward is minimised.